It Won’t Be A Shock To See Another Bank Fail Soon

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

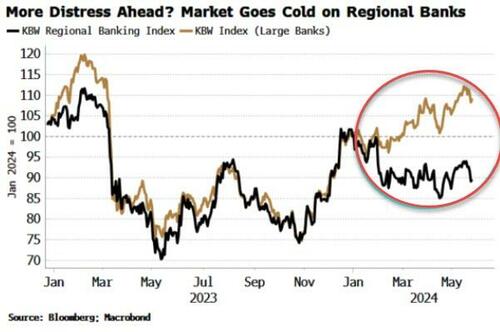

US regional banks’ deposits recently made new highs, exceeding the level prior to SVB’s collapse. But that’s far from an all clear. Exposure to commercial real estate continues to rise and delinquencies on the underlying loans is mounting. Hold-to-maturity bank portfolios are losing more money as yields increase, while small banks’ shares are weakening, significantly underperforming those of larger banks. Those conditions also preceded SVB’s bankruptcy last March.

The Federal Reserve has become adept at putting out fires in recent years. However, like the now-banned magic candles that re-lit after being blown out, fires can reignite. A full-scale banking crisis is unlikely, especially among the large banks, but there remain sufficient fragilities in the regional banking sector that could still deliver a nasty shock with reverberations across markets.

The Fed can rejoice in its success in preventing a wider banking crisis after Silicon Valley Bank’s failure. Deposits in small banks have now fully recovered. The Bank Term Funding Program, and a blanket deposit-guarantee for SVB and Signature Bank – which went down soon after Silicon – healed confidence in the sector.

But although the Fed feels assured enough to retire the BTFP, there is still something rotten in the state of Denmark: regional banks’ exposure to commercial real estate – the sector’s Achilles’ heel.

Small banks have always had a much larger exposure to CRE than large banks, but in the years before the pandemic their exposures tracked each other closely.

However, over the last two years small banks have doubled down on their CRE exposure to almost a third of assets – with barely a pause after SVB – while large banks have reduced theirs down to 6.5%.

Large banks’ actions are sounding the more savvy. CRE has faced huge challenges in the wake of the pandemic and a more home-centered economy. Delinquency rates in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) are rising again after their post-lockdown recovery, especially in the office and lodging sectors.

Not all CRE is bad, and not all banks will find themselves in trouble from souring commercial loans. But it is highly conceivable some will. Those with most exposure to office space, given rising delinquency rates, and to multifamily residential due to collapsing apartment prices, are a good place to start.

Furthermore, banks that make lots of loans quickly often run into issues down the line as underwriting standards can slip in haste (or are willfully overlooked to gain market share). Thus another first approach is to look at the banks who have seen their exposure to CRE rise the most since SVB’s bankruptcy.

Perhaps not uncoincidentally, some of the most shorted regional banks are those that have seen the fastest growth in commercial real estate loans, including Arkansa-based Bank OZK and BOK Financial Corporation.

The straw that broke the duration-camel’s back last year was a rise in interest rates, decimating underhedged or unhedged bond portfolios. SVB’s collapse came after a fairly rapid 50 bps rise in yields to over 4%.

The market was able to estimate losses on SVB’s AFS (available for sale) and HTM (hold to maturity) portfolios. Once this began to significantly exceed shareholder’s equity, the writing was on the wall. The shares kept sliding, and the fastest and largest bank run ever seen took place, sealing SBV’s fate.

Source: IMF

Banks’ ownership of HTM assets, which don’t have to be marked to market and whose losses are amortized, have barely fallen in the aggregate since last year. SVB had the highest proportion of HTM assets to securities held, nudging 80%.

Yields have been rising again, with the total return for Treasuries down more than 2% year-to-date and falling. Unrealized losses on HTM portfolios are still large, at $475 billion at the end of 2023, according to the FDIC (ZH: Actually they rose to $517 billion as reported yesterday in Q1).

Source: FDIC

Overall, regional banks’ total exposure to CRE plus HTM assets is higher than it was in March 2023. And losses on CRE and duration are making themselves felt, with the average operating income in the regional-bank sector (on a four-quarterly rolling basis) slipping to as low as it was before the pandemic, and a third lower than just before SVB.

Uninsured deposits were another system fragility that doomed SVB, Signature and First Republic (with NYCB recently hitting some major turbulence after acquiring Signature last year). Close to 90% of SVB and Signature’s deposits were not covered by FDIC insurance. This remains a major vulnerability for the small-bank sector, with the percentage of insured deposits for savings banks and associations (many of which come under the regional-bank category) basically unchanged since last March.

If another bank goes to the wall, the market will look to the Fed to restore stability. The BTFP was a major part of the initiative after SVB, allowing banks to swap USTs, agency debt and other high-quality collateral at par for loans of up to one year. The Fed stopped issuing new BTFP loans in March as it was being used mainly as an arbitrage.

Either way, the reintroduction of such a facility in the wake of another bank failure or failures rests on the banks having a sufficient ownership of “shiftable” securities the Fed is willing to accept. But smaller banks’ proportion of USTs and agency debt to total assets has continued fall, in contrast to large banks.

Einstein’s definition of insanity was doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different outcome. Smaller banks in the US continue to lose money on commercial real estate, face heavy losses on securities portfolios as yields push higher, and are just as exposed in the aggregate to bank runs from uninsured deposits. Sanity thus demands being ready for more bank failures.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 05/30/2024 – 08:45

Share This Article

Choose Your Platform: Facebook Twitter Linkedin